Brief History

- The oldest mancala board discovered was in Jordan, dug into the floor of a Neolithic dwelling that was converted into a Roman bath house. There is early evidence that the game has been around since 2nd century AD. It is mentioned in a book of songs from the 10th century in Mecca

- The Mills Games, 3, 6, 9, 12, and Lasker are found in evidence around the world, with one of the oldest diagrams of 12 Mills found in Egypt in 1400 BCE. There is evidence of boards carved into bath houses, homes, tables, church pews, roof tiles, and tapestries throughout history. It is called by many different names in different cultures, commonly know as Merels, Mills, or Morris baed on the Latin term, mareculus, the diminutive of man or the Latin word, merellus, meaning “game piece”.

Mancala Rules

- To have the most tokens in your mancala at the end of game

Set Up: Each player sits opposite each other, the long sides with six wells per side facing a player. The large well on each side is the “mancala” for each player. The mancala on the right is each player’s designated mancala.

Game Play: On each turn, a player will take all the tokens from any well. Moving counterclockwise, place one token in each well until you run out. This includes placing one in your own mancala, but NOT your opponent’s mancala. Capture any of your opponents tokens you can. Once the turn completes, it alternates to the other player.

Capturing Your Opponent’s Tokens: If you place the last token of your turn in an empty well on your side of the board, you captur all the tokens in the well on the opposite side of the board. Place all the captured tokens and the capturing token into your own mancala. If your last stone lands in your own mancala, you may tak another turn.

Winning the Game: As soon as all wells on one side of the game board are empty, the game is over. Any remaining tokens on the other side belong to the player whose side it is. The person with the most tokens in their mancala or remaining on their side of the board wins the game.

9 Mills or 9 Mens Morris

- To create “mills” of three pieces in a row, reducing your opponent’s pieces to two.

Set Up: Each player has nine pieces of different colours, shapes or markings, and an empty playing board.

Game Play: Decide who will go first. Players then take turns placing their pieces on the board. Pieces can be placed anywhere but may not share the same point. If a player puts three of their own pieces in a single, unbroken line, it is called a mill. For every mill formed, that player may remove one of their opponent’s pieces, starting with pieces not currently part of a mill.

Once all the pieces are on the board, each player takes turn moving their pieces around to create mills. Pieces may only move to an adjacent point connected by a line. They cannot jump pieces. The goal is to keep making mills. Mills can be broken and reformed by moving out of the mill and then back into it. Each time a mill is formed, a piece may be taken from the opposing player.

Flying: Once you are reduced to three pieces, you may “fly” around the board, moving your piece to any unoccupied point on the board, including jumping over pieces.

Winning the Game: When a player is reduced to two pieces, the game is over and the player with the most pieces remaining on the board is declared the winner.

12 Mills or 12 Mens Morris

- To create “mills” of three pieces in a row, reducing your opponent’s pieces to two.

Set Up: Each player has twelve pieces of different colours, shapes or markings, and an empty playing board.

Game Play: Decide who will go first. Players then take turns placing their pieces on the board. Pieces can be placed anywhere but may not share the same point. If a player puts three of their own pieces in a single, unbroken line, it is called a mill. For every mill formed, that player may remove one of their opponent’s pieces, starting with pieces not currently part of a mill.

Once all the pieces are on the board, each player takes turn moving their pieces around to create mills. Pieces may only move to an adjacent point connected by a line. They cannot jump pieces. The goal is to keep making mills. Mills can be broken and reformed by moving out of the mill and then back into it. Each time a mill is formed, a piece may be taken from the opposing player.

Flying: Once you are reduced to three pieces, you may “fly” around the board, moving your piece to any unoccupied point on the board, including jumping over pieces.

Winning the Game: When a player is reduced to two pieces, the game is over and the player with the most pieces remaining on the board is declared the winner.

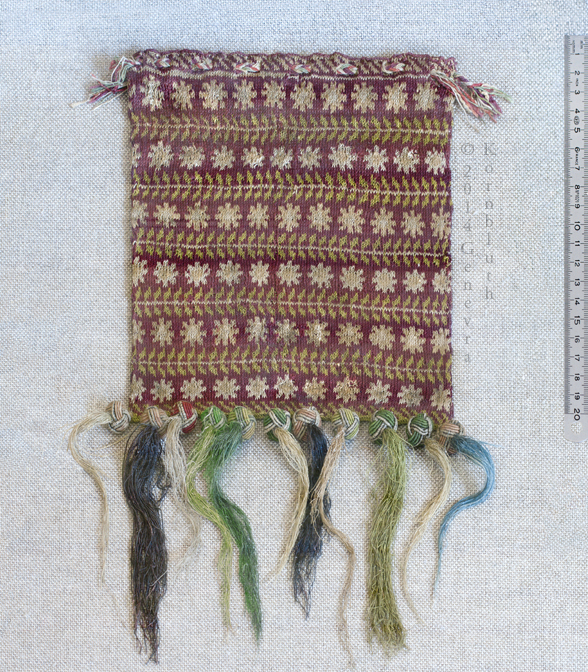

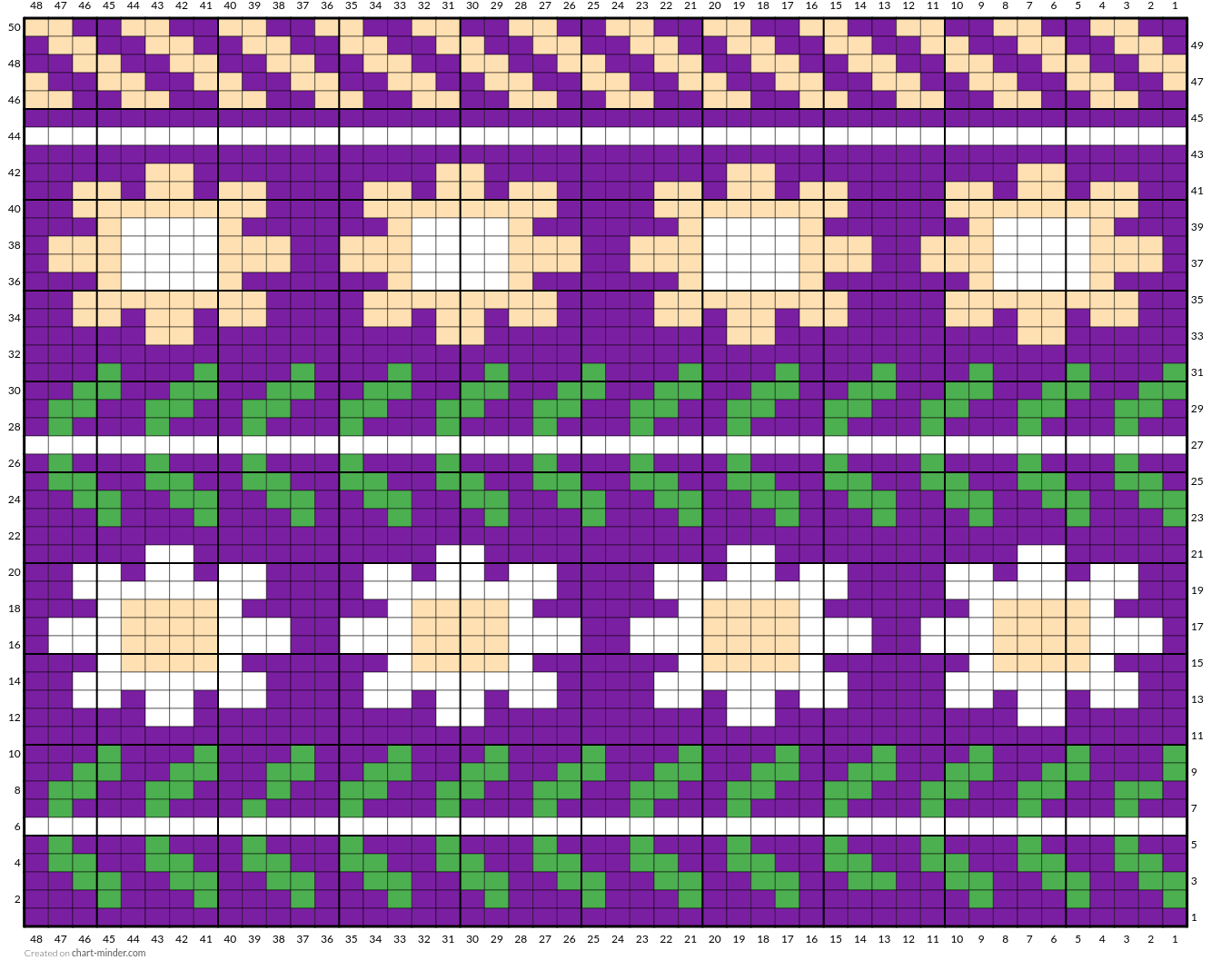

Virgin with Child,

Virgin with Child,  Chart created based on high resolution photos of extant, made on

Chart created based on high resolution photos of extant, made on